2018 Year-End Tax And Estate Planning Summary

For several years, we have stated in this year-end article that there were not significant changes to the individual income tax provisions during the preceding year. 2018, however, is different. In December 2017, Congress passed, and the President signed the Tax Cut and Jobs Act (the “Act”) making significant changes to the tax laws, including provisions related to individual taxation. Most of these changes became effective in 2018.

Rate Reduction

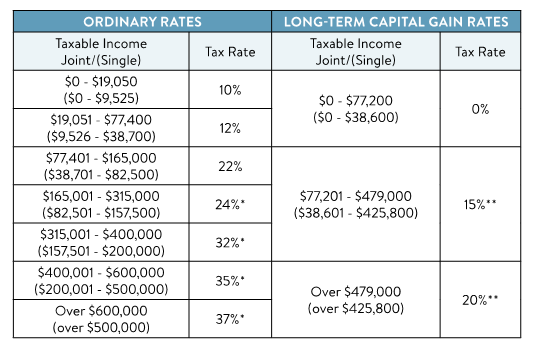

The centerpiece of the legislation was a reduction in tax rates. The top rate was reduced from 39.6% to 37%. In addition, the 15%, 25%, 28%, and 33% brackets were replaced by new 12%, 22%, 24%, and 32% brackets.

As has been true for some time, short-term capital gains continue to be taxed at ordinary rates. Long-term capital gains and qualified dividends continue to be taxed at rates of 0%, 15% and 20%. However, these rates now have their own brackets and are no longer tied to the ordinary income brackets. For 2018, the ordinary and long-term capital gain rates are:

Increased Standard Deduction

In addition to reducing rates, the Act significantly increased the standard deduction amounts. For 2018, the standard deduction is $24,000 (increased from $12,700) for married couples, $12,000 (increased from $6,350) for single filers; and $18,000 (increased from $9,350) for individuals filing as head of household.

Individuals can either itemize their deductions or claim a standard deduction, whichever is greater. By increasing the standard deduction amount, many taxpayers that previously itemized their deductions will now be able to claim the standard deduction, thus, significantly simplifying those taxpayers’ reporting obligations. It has been estimated that 18 million households will itemize deductions in 2018 versus 46 million last year.

Revenue Raisers in the Act

Reduced rates and the increased standard deduction benefit all taxpayers. However, to help pay for some of the costs associated with these benefits, the Act eliminated the personal exemption and reduced or eliminated several popular deductions.

Elimination of Personal Exemption

Previously, taxpayers could claim an exemption for themselves and each of their dependents. In 2017, the exemption amount was $4,050/person. For a family of 4, that equated to a reduction in taxable income of $16,200. Beginning in 2018, the personal exemption has been eliminated.

Cap on State & Local Tax Deduction

The most talked about change to the itemized deduction rules is the cap on the deduction for state and local taxes, including real estate taxes on primary and vacation residences. Previously, individuals could deduct all state and local income and real estate taxes paid.

Beginning in 2018, the deduction for state and local taxes is capped at $10,000. Many individuals pay significantly more than $10,000 in state and local taxes. In fact, for most higher income taxpayers, state and local taxes represent their single largest deduction. This is especially true for individuals in high tax states, such as Illinois.

Some states have already enacted legislation to counter the effectiveness of the cap on deductions for state and local taxes. Beginning in 2019, New York and New Jersey will introduce programs wherein individuals can contribute to newly created state charitable funds (for which they could claim a federal charitable deduction) and, in turn, will receive a credit that they would utilize to offset their state tax obligation. The Internal Revenue Service has already stated that they will be issuing regulations to curtail efforts to get around the cap on the deduction for state and local taxes.

Charitable Deductions

The laws related to charitable deductions were largely untouched by the Act. However, the legislation created a new 60% charitable deduction limit for cash contributions to public charities. In other words, individuals can now deduct cash contributions to public charities up to 60% of their adjusted gross income. In the past, cash contributions to public charities were capped at 50% of adjusted gross income.

Notwithstanding the increased cap on charitable deductions, many people will no longer receive a tax benefit from their charitable contributions. As noted above, millions of people that previously itemized their deductions will now begin claiming the standard deduction. Individuals whose total itemized deductions are close to the new standard deduction amount may consider combining their charitable contributions.

For example, a married couple filing a joint return may have itemized deductions totaling $23,000, including $5,000 of charitable gifts. Because their itemized deductions total less than the $24,000 standard deduction, the couple will simply claim the standard deduction and will receive no tax benefit for their charitable giving. A couple in this situation may consider combining 2-years of gifts into a single year and not make any gifts in the subsequent year. As such, in one year they would have itemized deductions of $28,000 ($23,000 + additional gifts of $5,000) and, in the subsequent year, their itemized deductions would total $18,000 and they would simply claim the $24,000 standard deduction.

IRA Charitable Rollover

In 2016, the provision allowing individuals age 70½ and older the ability to distribute up to $100,000 annually from an IRA to a charitable organization was made permanent. By distributing funds directly from your IRA to charity, the distribution is not included in the account owner’s taxable income (and the account owner is not allowed to claim a tax deduction for the charitable contribution). The IRA Charitable Rollover remains available after passage of the Act.

Mortgage and Home Equity Indebtedness

The Act limits the deduction for interest incurred on home acquisition indebtedness to $750,000. Previously, homeowners were allowed to deduct mortgage interest on up to $1 million of home acquisition indebtedness, although the $1 million limitation continues to apply for loans that were in existence at time of the Act’s passage. Beginning in 2018, the previous deduction for interest on up to $100,000 of home equity indebtedness is no longer allowed.

Medical Expenses

Medical expenses continue to be deductible under the Act. For 2018, you will be able to deduct medical expenses to the extent they exceed 7.5% of your adjusted gross income. Beginning in 2019, medical expenses will only be deductible to the extent such expenses exceed 10% of your adjusted gross income. Prior to passage of the Act, medical expenses were deductible to the extent expenses exceeded 10% of adjusted gross income. The Act increased the deductibility of these expenses in 2017 and 2018.

Miscellaneous Itemized Deductions Eliminated

Under prior law, miscellaneous itemized deductions were deductible to the extent such expenses exceeded 2% of adjusted gross income. Miscellaneous itemized deductions include unreimbursed employee expenses, investment management fees, and tax preparation fees. Beginning in 2018, the deduction for miscellaneous itemized deductions has been eliminated.

Other Provisions of Note

529 Plans Expanded

529 plans are popular tools to save for college expenses. Under the Act, distributions from 529 plans can now cover up to $10,000 of education expenses for designated beneficiaries enrolled at a public, private or religious elementary or secondary school. Note — Check your state law before distributing funds from a 529 plan for elementary or secondary school expenses. While the Act provides that distributions would not be taxable for federal purposes, many states, including Illinois, do not consider elementary or secondary school expense “qualified education expenses” and will subject such distributions to state income tax.

Alternative Minimum Tax

The Alternative Minimum Tax was not eliminated, but the AMT exemption amount was increased to $109,400 for married couples ($70,300 for single filers). Also, these exemption amounts are only subject to phase-out for married couples with adjusted gross income of more than $1 million ($500,000 for single filers). This, combined with changes to the itemized deductions rules, should result in fewer middle-income households being subjected to AMT. The AMT will continue to be an issue for high-income taxpayers.

Alimony

The Act eliminates deductions for alimony payments required under divorce or separation agreements executed after December 31, 2018. Alimony recipients will no longer have to include alimony in taxable income. The Act’s treatment of alimony payments also applies to divorce or separation decrees that are modified after December 31, 2018, if the modification specifically states that the new treatment of alimony payments now applies. For individuals who must pay alimony, this change may be expensive. Child support payments remain non-deductible by the payor.

Estate & Gift Taxes

The Act also made a significant impact on the estate and gift tax regime. While the estate and gift taxes were not eliminated, the Act doubled the unified exemption amount. Under prior law, the exemption was scheduled to be $5.59 million in 2018. Pursuant to the Act, the exemption amount increased in 2018 to $11.18 million ($22.36 million for married couples). The top tax rate for estate and gift tax purposes remains at 40%.

The generation-skipping transfer (“GST”) tax is still in place. Generally, the tax applies to lifetime and death-time transfers to or for the benefit of grandchildren or more remote descendants. For 2018, the rate is a flat 40 percent. The tax is in addition to any gift or estate tax otherwise payable. As with the gift and estate tax, each taxpayer is allowed an $11.18 million GST tax exemption for 2018.

Consider Lifetime Gifts that take Advantage of both the Gift Tax Exemption and GST Exemption

Many clients utilize a portion or all of their gift tax exemption by structuring long-term GST exempt trusts benefiting multiple generations. Such trusts will remain exempt from all gift and estate tax as long as the trust remains in existence. Under Illinois law, such trusts can last in perpetuity, thereby allowing you to create a family “endowment fund” for your children, grandchildren and future descendants.

The increase in the exemption amount to $11.18 million ($22.36 million for married couples) provides an opportunity for those clients that had already fully utilized the old exemption amount to consider additional gifting.

Annual Exclusion Gifts

In 2018, you may make a gift of $15,000 to any individual and certain trusts without any gift tax consequences. Married individuals may make gifts of up to $30,000. Gifts may be made outright or in trust and may be in the form of cash, securities, real estate, artwork, jewelry or other property. Giving property that you expect to appreciate in the future is an excellent way of utilizing your annual gift tax exclusion because any post-gift appreciation is no longer subject to gift or estate tax. To take advantage of the gift tax annual exclusion for 2018, gifts must be made by December 31. Gifts over $15,000 or gifts that will be “split” between spouses must be reported on a gift tax return, which must be filed in April 2019. The annual exclusion amount is expected to remain at $15,000 in 2019, $30,000 for married couples.

Payment of Tuition and Medical Expenses

In addition to annual exclusion gifts, you may pay tuition and medical expenses for the benefit of another person without incurring any gift or GST tax or using any of your gift or GST tax exemption. These payments must be made directly to the educational institution or medical facility. There is no dollar limit for these types of payments and you are not required to file a gift tax return to report the payments.

Take Advantage of Today’s Low Interest Rates

Interest rates are rising, but they are still at historically low levels. Low interest rates enhance the benefits of several gift and estate planning strategies. One such strategy is the “grantor retained annuity trust” or GRAT. A GRAT is an irrevocable trust to which a donor transfers property and retains the right to receive a fixed annuity for a specified term. At the expiration of the term, the property usually passes outright or in trust for the benefit of descendants or other named beneficiaries. The amount of the gift resulting from the transfer of the property to the GRAT is the present value of the remainder interest that passes to the beneficiaries at the end of the term. Under the valuation methods adopted by the IRS, the lower the interest rate at the time of the gift, the lower the present value of the remainder interest and the smaller the amount of the gift that must be reported to the IRS. Interests in marketable securities with high growth prospects are often ideal properties to transfer to a GRAT. While there has been considerable discussion about disallowing “zeroed-out” GRATs and requiring a minimum GRAT term of 10 years, Congress has not taken any action in this respect. As a result, GRATs remain a very attractive planning opportunity.

Example –Individual funds a GRAT with $1 million. The GRAT’s term is 5 years and its assets appreciate at a rate of 6%. Assuming the applicable IRS interest rate is 3.6% (the rate in effect for November 2018) and the GRAT is “zeroed-out”, the remainder value of the GRAT assets at its termination would be approximately $86,000. In other words, the GRAT structure would have allowed the individual to transfer assets valued at approximately $86,000 to his children or designated beneficiaries without incurring any gift tax obligation or utilizing any of his or her lifetime exemption amount. If the assets inside the GRAT were to appreciate at a rate of 8%, the remainder available to the trust’s beneficiaries would be approximately $166,000.

Low interest rates also make sales to “defective” grantor trusts more attractive. Under this strategy, a taxpayer creates a trust, typically for his or her spouse and descendants. The taxpayer then sells assets to the trust taking back a note requiring the trust to repay the taxpayer in installments. The trust is structured so that it is ignored for income tax purposes, resulting in no income tax consequences upon the sale. The interest paid on the note is typically at the applicable federal rate in effect at the time of the sale. The lower the interest rate on the note, the greater the amount of assets that will accumulate in the trust free of estate, gift and GST taxes.

For more information, please contact Greg Winters at 312/840-7059 or gwinters@burkelaw.com.

Related Professional

- Partner

Related Practices & Industries

Sign-Up

Subscribe to receive firm announcements, news, alerts and event invitations.